In Progress

Archive for the Patient Category

Depending on your age and other medical conditions, your doctor might suggest a liver transplant if you’ve developed decompensated cirrhosis or liver cancer.

A liver transplant is surgery to give you a healthy liver from another person. You may get a whole new liver or just part of a new liver. The new liver may come from someone you know. Or it may come from a stranger or a person who’s died.

The waiting time for a new liver may be uncertain and stressful. The sickest patients receive highest priority. Priority is based on the severity of the liver disease as measured by a MELD (model for end-stage liver disease) score. This is simply a score calculated from four different blood tests. It helps liver transplant doctors determine which patients are at greatest danger of dying and should therefore receive transplants first.

The Procedure

A liver transplant is a major surgery that lasts 6 to 8 hours. To do the surgery, the doctor makes an incision (cut) in your upper belly. The doctor removes your liver and all its attachments. Next, they connect the blood vessels and bile duct of the new liver to your blood vessels and bile duct. The surgery is finished by closing the incision with stitches or staples. You will then be taken to the intensive care unit for close monitoring until the doctors feel you are well enough to go to the surgery unit.

After the Procedure

After a liver transplant, regular lab tests are important to check for signs of the body rejecting the new liver. Sometimes liver biopsies are also done to see if rejection is occurring. You can expect to stay in the hospital for 1 to 4 weeks and sometimes longer if there are complications. Your staples will be removed about 3 weeks after your surgery. Before you go home, your healthcare team will give you detailed information about your follow up care. You’ll need to take immune suppressing medicines and be carefully monitored for life. However, the monitoring will reduce in frequency the further out you are from your transplant.

Risks and Side Effects

People who get a liver transplant have to take drugs that suppress their immune system to prevent their body from rejecting the new liver. These drugs have their own risks and side effects, especially the risk of serious infections.

For those who had liver cancer, these drugs might allow any remaining cancer to grow faster than before. This is because the drugs suppress the immune system.

Some of the drugs used after a liver transplant can also cause:

- diabetes

- high blood pressure

- high cholesterol

- weakening of the bones and kidneys

- a new cancer

Liver transplants have been hugely successful in saving the lives of patients with end-stage liver disease. Although complications may occur that will have to be managed, 85 – 90% of patients will survive the first year. Most survive to five years and beyond.

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References:

A serious complication of cirrhosis is liver cancer. People with cirrhosis have a higher risk of developing liver cancer.

References

This material was adapted (with permission) from:

US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration

When to Get Help

Go to the nearest emergency department, or have someone call 911 if you:

- are vomiting blood or something that looks like coffee grounds

- have black or tar-like bowel movements

These are signs that varices may have begun to bleed.

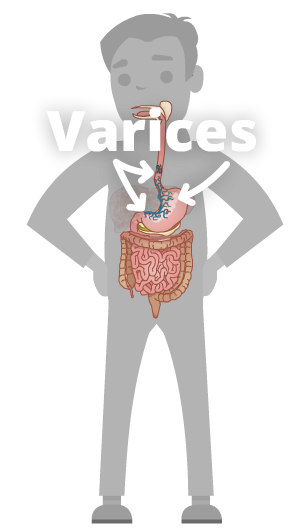

What are Varices?

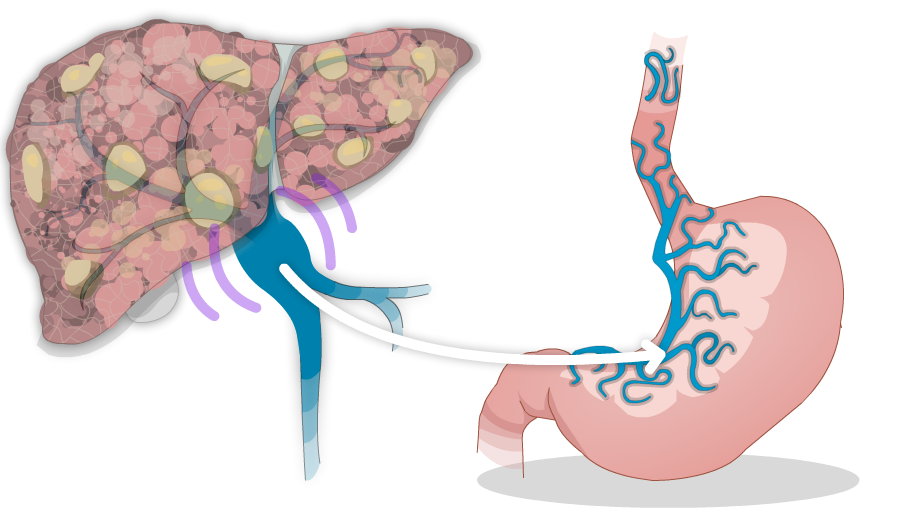

When pressure in the portal vein gets too high, it can cause pressure to rise in other blood vessels. This can make the veins in your esophagus (food pipe), and stomach swell. These swollen veins are called varices. In some cases, these veins can get so swollen that they burst. This causes bleeding inside your esophagus and stomach, which is dangerous.

When pressure in the portal vein gets too high, it can cause pressure to rise in other blood vessels. This can make the veins in your esophagus (food pipe), and stomach swell. These swollen veins are called varices. In some cases, these veins can get so swollen that they burst. This causes bleeding inside your esophagus and stomach, which is dangerous.

Symptoms

The problem with varices, is that they don’t cause symptoms until they burst open and bleed. Many people have varices and don’t know that they do. Sometimes they’re found during an upper endoscopy (also known as gastroscopy).

The more severe the liver damage and the larger the varices, the greater risk you have for bleeding varices. Bleeding varices can be a life-threatening emergency. After varices have bled once, there’s a high risk of bleeding again.

Treatment

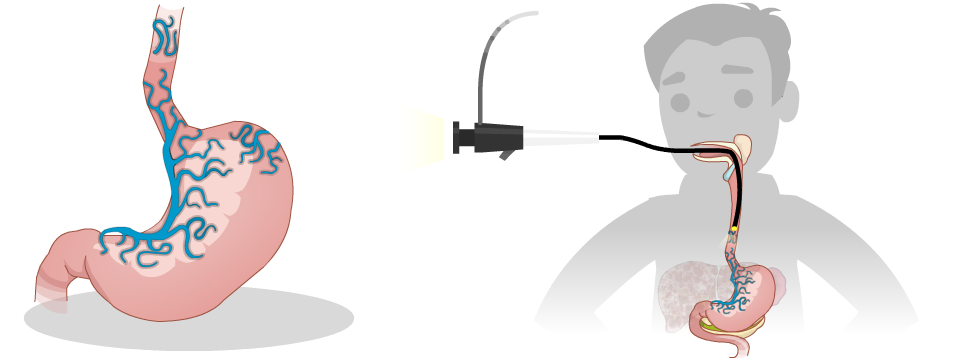

Upper Endoscopy (Gastroscopy)

Your healthcare team will look at the results of your blood and other tests to determine your risk of having varices. If you are at higher risk, your healthcare team may want you to have a procedure called an upper endoscopy (gastroscopy). An upper endoscopy involves inserting a tiny camera through your mouth to look down into your esophagus and into your stomach. If you have varices, they can be tied off with tiny rubber bands during the procedure (called banding).

If your first upper endoscopy didn’t find any varices, you will likely have another one again in 1 to 3 years. If you have varices, you may need more frequent upper endoscopies. You’ll also need to have an upper endoscopy more often if you’ve had bleeding varices.

Medication (nonselective beta-blockers)

Your healthcare team may also prescribe blood pressure medicine called nonselective beta-blockers to help lower the risk of bleeding from varices. If you take this medicine, you’ll need to check your blood pressure and pulse regularly. If you feel dizzy, lightheaded, or fall, let your doctor or nurse know.

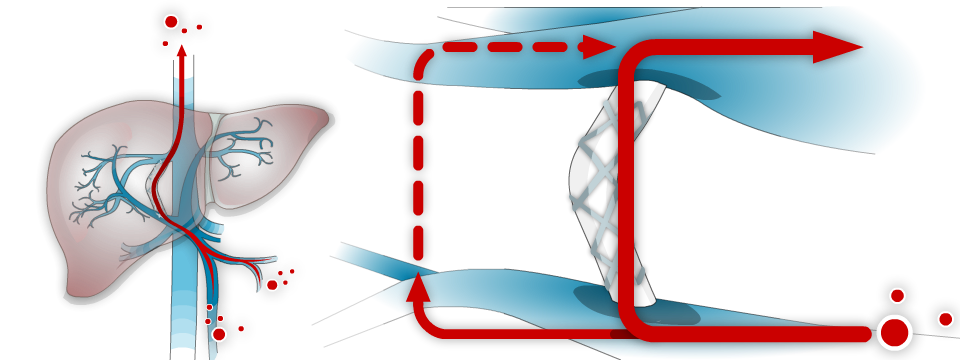

TIPS (a shunt used to decrease pressure in the portal vein)

In more severe cases, an TIPS procedure may be required to stop or prevent future bleeding. This is a procedure done by an interventional radiologist in a specialized hospital.

For more information on these treatments, please click the links below:

Self Care Tips:

- Check the colour of your bowel movements (stool) for signs of bleeding. If there’s blood in your stool, it may be black or look like tar

- Attend upper endoscopy appointments when recommended by your healthcare provider

If you take blood pressure medicine:

- check your blood pressure and pulse 2 to 3 times a week. Rest for at least 5 minutes before you check these measurements

- Record your measurements in a notebook or app on your phone

Let your healthcare provider know if:

- your pulse is less than 50 beats per minute

- the first (or top) number of your blood pressure is lower than 90

- you are dizzy, lightheaded, or fall

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References:

When to get Help

Only mild symptoms of confusion (hepatic encephalopathy) should be managed at home.

Go to the nearest emergency department, or have someone call 911 if you:

- have severe confusion or sleepiness

- can’t speak, walk properly, or follow directions

- have a fever

- have severe nausea and vomiting

What is Hepatic Encephalopathy?

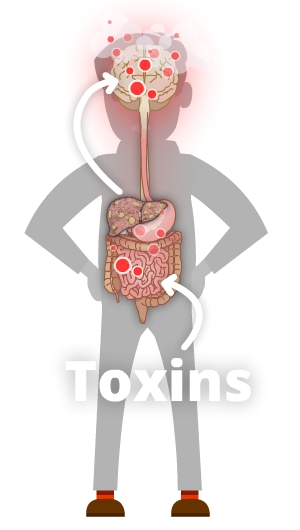

When the liver’s been damaged by cirrhosis, it might not be able to get rid of toxins such as ammonia. As a result, ammonia and other toxins may build up in your bloodstream and brain. This causes a problem called hepatic encephalopathy (pronounced “en-sef-a-lop-a-thee”). You may hear your healthcare team call it HE for short. When you have HE, toxins build up which can cause confusion and other symptoms.

Causes

Encephalopathy is most likely to occur in people who have high pressure in their portal vein (portal hypertension). It may also occur in people who have severe acute liver damage (liver damage that happens suddenly) but no portal hypertension.

Also, a procedure called TIPS that is used to lower portal hypertension by shunting blood flow around the liver can increase your risk for encephalopathy.

Other things that might contribute to encephalopathy include:

- abnormal levels of electrolytes

- constipation

- not getting enough fluids to drink or loosing fluids too quickly (dehydration)

- internal bleeding

- infection

- medicines like pain killers and sleeping pills

Symptoms

Symptoms of encephalopathy might include:

- coma

- disorientation (not remembering where you are or what’s happening)

- difficulty remembering the right words to say

- drowsiness

- hand “flapping”

- sleep pattern changes

- feeling irritable

- trouble concentrating

- poor short-term memory

- having tremors

Treatment

Your Support Network

Share what you learn about hepatic encephalopathy with your caregivers, friends, and loved ones. This is important because having encephalopathy can make it hard for you to care for yourself at times, and you may need extra support. Your support network can help you watch for emergency warning signs. For example, if they notice you’re really confused or have trouble waking up, they can call 911 or take you to the nearest emergency department.

Lactulose

In most situations, encephalopathy is treated with a medicine called lactulose. Lactulose is a laxative syrup that makes your bowels move more often and also makes your bowel movements more acidic. This helps your body to get rid of toxins like ammonia from your body.

If you are taking lactulose, you should take enough so that you are having 2 or 3 soft bowel movements each day. If you take too much you will get diarrhea, but if you don’t take enough you will develop encephalopathy symptoms. You should increase the amount you are taking if you are not having enough bowel movements. Finding the right balance for you is the key. You can get more information about lactulose (including potential side effects) from your pharmacist.

Rifaximin (Zaxine, Xifaxan)

Another treatment for encephalopathy is rifaximin. Rifaximin is an antibiotic that stays in your digestive system and changes the bacteria in your gut so they make less toxins like ammonia. Rifaximin comes as a pill and is usually taken two times a day. You can take it with or without food. You can get more information about rifaximin (including potential side effects) from your pharmacist.

Self Care Tips:

If you are being treated for hepatic encephalopathy:

- Avoid medicines that can make you sleepy

- Record the number of bowel movements you have each day in a notebook or app on your phone

- Take enough lactulose so you have 2 to 3 medium to large, soft bowel movements a day.

- Don’t take more lactulose than you need because it may make you dehydrated.

- If you develop a mild increase in your encephalopathy symptoms, take more lactulose (as long as you are not having diarrhea, fever, or signs of bleeding).

Let your healthcare provider know if you:

- have trouble adjusting your dose of lactulose

- feel tired, sleep more, or your sleep patterns change so you’re up at night and sleep during the day

- have trouble concentrating or remembering things

- have a change in your personality

- notice shaking of your body (called a tremor) or are unsteady (feel like you may fall)

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References:

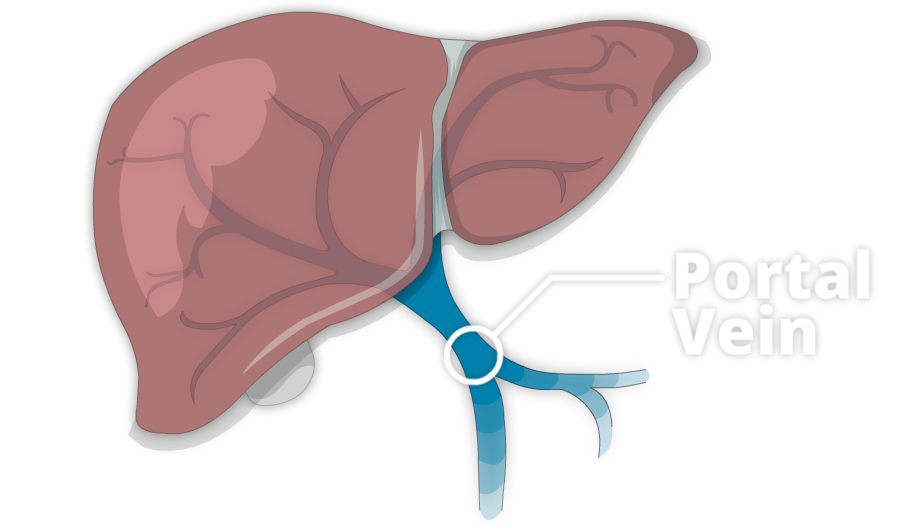

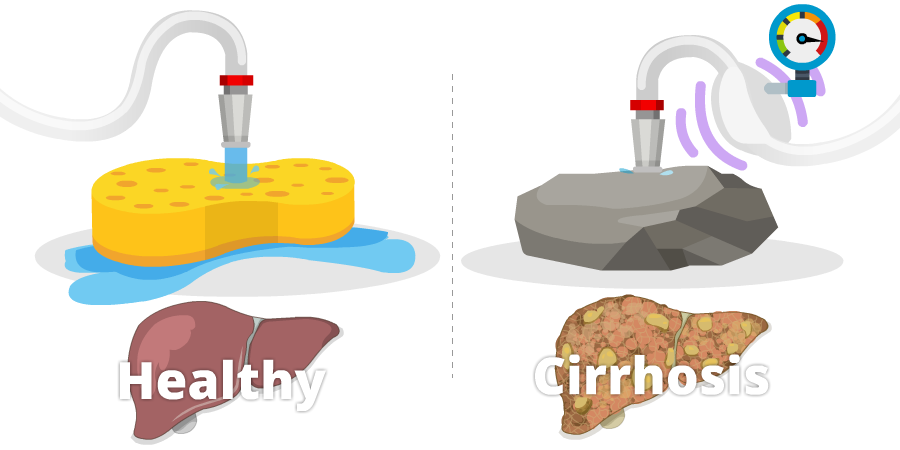

A healthy liver is soft, like a sponge. It gets most of its blood supply from a large blood vessel called the portal vein.

When the liver is soft, blood can flow into it easily, like water from a hose pouring into a sponge. Imagine that sponge gets hard like a rock. Water from the hose can’t flow in as easy and pressure builds up in the hose. Just like the hose, pressure in the portal vein can build up when the liver becomes hard and blood can’t flow into it very well.

This condition is called portal hypertension

To relieve pressure in the portal vein, the blood takes detours around the liver in other veins. Some of these veins are in the esophagus, the tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach. Other veins are in the stomach.

The increased pressure can also makes your spleen bigger. One of the jobs of the spleen is to control the number of platelets you have in your body. Platelets help your blood to clot. When the spleen gets bigger and can’t do its job properly, you may notice you bruise more easily or it takes longer to stop bleeding.

Portal hypertension is important because it can lead to major complications of cirrhosis like ascites and varices.

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References:

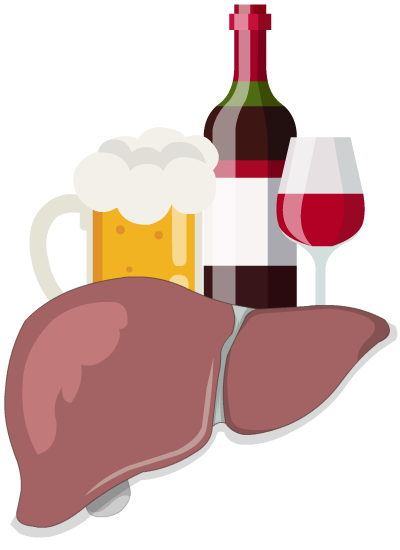

Alcohol & the Liver

The liver processes everything a person ingests, including alcohol. It can only detoxify so much alcohol at a time. If the liver is overwhelmed, excess alcohol can affect the brain, heart, muscles, and other tissues of the body. Daily consumption of alcohol as well as binge drinking (e.g., heavy drinking on weekends) can be particularly harmful to your liver. Any type of alcohol including hard liquor, beer, or wine, can damage the liver.

The liver processes everything a person ingests, including alcohol. It can only detoxify so much alcohol at a time. If the liver is overwhelmed, excess alcohol can affect the brain, heart, muscles, and other tissues of the body. Daily consumption of alcohol as well as binge drinking (e.g., heavy drinking on weekends) can be particularly harmful to your liver. Any type of alcohol including hard liquor, beer, or wine, can damage the liver.

When the liver has too much alcohol to handle, normal liver function may be interrupted. Over time, liver cells may be altered or destroyed. Alcohol-related liver disease is divided into three types. All three types can occur in one person at the same time.

- Alcohol related fatty liver disease. Anyone who drinks alcohol heavily will develop a condition in which liver cells are swollen with fat and water. This is called alcoholic fatty liver disease.

- Alcohol associated hepatitis. Heavy drinking can also lead to inflammation in the liver, called alcoholic hepatitis. Advanced alcoholic hepatitis can result in serious illness including death. This may occur before or after cirrhosis develops. Patients with alcoholic hepatitis have symptoms such as fatigue, poor appetite, jaundice (yellowing skin or eyes), or even fever. They are generally hospitalized.

- Alcohol related cirrhosis. This is advanced scarring of the liver, usually caused by years of drinking alcohol.

For people with chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or fatty liver disease, alcohol increases damage to the liver. It speeds up the development of cirrhosis.

Diagnosis

You may have advanced liver disease before you notice any symptoms. By then, it might be too late to do anything about it. So, it’s important to see your doctor and be honest about how much alcohol you drink. Through regular physical exams and blood tests, your doctor will be able to detect early signs of liver damage from alcohol.

Treatment

Anyone with liver disease should NOT drink alcohol.

Anyone with liver disease should NOT drink alcohol.

Some people can improve their livers if they stop drinking entirely—even those who have already developed cirrhosis. When there’s no alcohol in the bloodstream, the liver cells are able to recover. The liver has a tremendous capacity to regenerate itself. In the majority of people who stop drinking alcohol, there’s a slow but noticeable improvement in how well their liver functions. If you choose to drink alcohol, less alcohol is best.

Nevertheless, for a few people, damage may be irreversible. There may be major health consequences or even death. The sooner alcohol is eliminated, the better the chance for recovery.

Note: The above sections were adapted (with permission) from content on the website of the Canadian Liver Foundation.

Get Support

It can be hard to cut down or quit drinking. Get support from people who care about you and want to help. Ask your family and friends to help you reach your goal. Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re having trouble cutting down.

There are also other resources to help you. Alberta’s Addiction Helpline is a toll-free, confidential service. The helpline can refer you to local support services related to addiction to alcohol.

Alberta’s Addiction Helpline 1-866-332-2322.

Use a Change Plan and Drinking Diary

One way to make any kind of change in your behaviour is to come up with a change plan. In the plan, list the goals you’d like to achieve. Outline the steps and challenges you’ll meet in reaching those goals, and figure out ways to overcome those challenges.

To keep track of how much you drink, use a drinking diary. Each day, record the number of drinks you have. At the end of the month, add up the total number of drinks you had each week.

Tips for Cutting Back

- Watch it at home. Keep no alcohol at home or only a small amount. Don’t keep temptations around.

- Drink slowly. When you drink, sip it slowly. Take a break of one hour between drinks. Drink water or non-alcoholic drinks after each drink with alcohol. Don’t drink on an empty stomach! Eat food when you’re drinking.

- Take a break from alcohol. Pick a day or two each week when you will not drink at all. Then, try to stop drinking for one week. Think about how you feel physically and emotionally on these days. When you succeed and feel better, you may find it easier to cut down for good.

- Learn how to say no. You don’t have to drink when other people drink. You don’t have to take a drink when it’s offered to you. Practice ways to say no politely. For example, you can tell people you feel better when you drink less. Stay away from people who give you a hard time about not drinking.

- Stay active. What would you like to do instead of drinking? Use the time and money you’d normally spend on drinking to do something fun with your family or friends. Go out to eat, see a movie, or go for a walk.

- Watch out for temptations. Watch out for people, places, or times that make you want to drink. Stay away from people who drink a lot, and avoid bars. Plan ahead of time what you will do to avoid drinking when you’re tempted.

- Don’t drink to cope with negative emotions. Don’t drink when you’ve had a bad day or you’re angry or upset. This is a habit you need to break if you want to drink less.

- Don’t give up! Most people don’t cut down or give up drinking all at once. Just like going on a diet, it’s not easy to change. This is okay. If you don’t reach your goal the first time, try again. Don’t give up! It will get easier.

Note: Much of this section was adapted from a handout by the National Institutes of Health last updated May 28, 2001.

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References:

This is a glossary of common medical terms related to cirrhosis and other liver diseases.

An abnormal build-up of fluid in the abdomen (belly).

See more: Ascites

Flapping movement of the hands, sometimes referred to as “liver flap”. This happens when the liver can’t remove toxins from the bloodstream, a condition called hepatic encephalopathy. The toxins affect the brain, which causes the hand flapping.

A growth that is not caused by cancer.

Medicines (like propranolol and nadolol) that lower blood pressure and heart rate. People with cirrhosis usually take them to lower the chance of developing complications and the risk bleeding from enlarged veins called varices.

See more: Medication safety, Portal hypertension

A substance produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder. Bile contains many different substances including salts, cholesterol, and bilirubin. After a meal, the gallbladder pumps bile into the first part of the small intestine to help with digestion. This also helps to break down fats.

A score that indicates how sick your liver might be. Based on this score, there are three stages:

- A: Mild

- B: Moderate

- C: Severe

If you’re in stage B or C, you should be considered for a liver transplant.

Many people with liver cancer also have cirrhosis. To treat the cancer, doctors need to know their patients’ CTP.

Scarring in the liver.

See more: What is cirrhosis?

A type of scan used to take pictures of inside the body. It uses computer-processed X-rays to make the pictures. People with cirrhosis might have a CT scan to see the liver and other structures inside the abdomen.

Water pills such as spironolactone (Aldactone®) and furosemide (Lasix®). These help the body eliminate extra fluid build-up. For people with cirrhosis, fluid most commonly builds up in the belly (ascites), legs (edema). or around the lungs (pleural effusion).

See more: Ascites

Changes in brain function, such as memory trouble, confusion or sleepiness, which happen when toxic substances (like ammonia) aren’t filtered by the liver.

See more: Hepatic encephalopathy

A procedure where a doctor inserts a thin, flexible viewing tube called an endoscope (or scope) to look at internal areas of your body. Examples of endoscopies include colonoscopy, cystoscopy, and upper endoscopy (gastroscopy). An upper endoscopy is the type endoscopy doctors use to look for varices (enlarged veins) in people with cirrhosis.

The tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach. Sometimes referred to as the food pipe.

Fever is usually defined as having a temperature of 38°C (100.4°F) or higher.

A temperature between 37.5°C (99.5°F) and 37.9°C (100.2°F) and feeling unwell is also a cause for concern in someone with cirrhosis.

A type of cancer that starts in the liver, also known as HCC.

See more: Liver cancer

Liver cells.

A soft, flexible tube that runs underneath your skin to an area in your belly to drain fluid called ascites.

Yellowing of the eyes and skin that shows the liver is malfunctioning. Jaundice is also a symptom of cirrhosis.

Surgery to remove part of the liver. This is sometimes done to treat liver cancer.

When a surgeon removes your liver and replaces it with either an entire liver from a deceased donor or a portion of a liver from a living donor.

See more: Liver transplantation

A scan used to look at internal structures of the body in more detail using magnetic fields and radio waves.

The MELD (model for end-stage liver disease) score is a scoring system based on lab tests. It helps determine how sick the liver is. Healthcare providers use MELD to rank the need and urgency for liver transplant. In general, a higher the MELD score means the liver is sicker.

A procedure used to drain fluid from the abdomen called ascites. people often call it a tap.

See more: Ascites

A procedure for removing samples of liver tissue. After freezing with a local anesthetic, the doctor inserts a small needle through the skin and into the liver. There’s a very small risk of bleeding from the biopsy and some discomfort, but it’s well-tolerated by most people. The needle removes 2 or 3 small samples of liver tissue.

The space between your internal organs and the wall of your abdomen. This is where ascites fluid builds up.

The vein that carries blood from your intestines to your liver.

See more: Portal hypertension

Anything that increases your chance of getting a disease.

Tiny veins that look like small red spiders on the face, chest, and arms. Spider angiomas can be a sign of cirrhosis.

A type of liver biopsy used for people who have a problem with blood clotting or a large amount of fluid in their abdomen (ascites). A small tube is inserted into the jugular (neck) vein, using X-rays to help guide the tube down into a large vein in the liver. Then the doctor uses a small needle passed through the tube to remove 2 or 3 small samples of liver tissue.

A type of scan that uses sound waves other vibrations to look at organs, vessels, and tissues inside your body.

A procedure where a doctor inserts a thin, flexible viewing tube called a gastroscope (or scope) to look in your esophagus (food pipe), stomach, and upper part of your small intestine. A gastrosocpy is the type endoscopy doctors use to look for varices (enlarged veins) in people with cirrhosis.

Enlarged veins in the lining of the esophagus and upper stomach. These are caused by increased blood pressure in the portal vein, a common complication related to having cirrhosis. Some people can also get varices in their rectum.

See more: Varices

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References:

Some lab tests are done after you’ve been diagnosed with liver damage. Other tests will continue on a regular basis. These tests will monitor your health and help you and your doctor decide what treatment is best for you, and if it’s working.

Regular Lab Tests

Normal Level in Adults: 30 – 130 U/L (Units Per Litre)

Alkaline phosphatase is also called ALP, or more commonly, alk-phos. It’s an enzyme produced in liver cells and in your liver’s bile ducts. The test for alk-phos is typically part of a liver panel.

Explanation of Test Results

- High alk-phos occurs when there’s a blockage within your bile ducts, or when there’s a buildup of pressure in your liver. These conditions are often caused by a gallstone or scarring in the bile ducts.

- Alk-phos is produced in other organs besides your liver. It’s also found in your bones and kidneys. It doesn’t necessarily reflect liver damage or inflammation.

Normal Level in Adults: 7 – 40 U/L (Units Per Litre)

ALT is one of many liver enzymes. It’s useful to detect ongoing activity like inflammation in your liver. When your liver cells are damaged, ALT leaks into your bloodstream, reaching a higher-than-normal level. ALT is a reasonably specific indicator of liver status.

Explanation of Test Results

- High ALT often means you have some liver damage, but it doesn’t show exactly how much. ALT won’t indicate the amount of scarring (fibrosis) in your liver, and it won’t predict how much liver damage may develop.

- ALT can rise and fall in small increments in most people. This doesn’t mean the liver is functioning better or worse. However, people can have cirrhosis and other severe liver disease and still have a normal ALT level.

(Note: ALT is also known as alanine transaminase.)

Normal Level in Adults: 5 – 40 U/L (Units Per Litre)

AST is another enzyme made by liver cells. Like ALT, AST leaks into your bloodstream when liver cells are damaged, reaching higher-than-normal levels. Unlike ALT, AST is also in other parts of your body including your heart, kidneys, muscles, and brain. When cells in any of these body parts are damaged, AST can be elevated.

Explanation of Test Results

- High AST often means you have some liver damage. But high AST with a normal ALT may mean the AST is coming from a different part of your body.

- AST doesn’t show exactly how much liver damage you might have or if your liver is getting better or worse. Normally, small changes in AST levels can be expected.

- As with ALT, people can have cirrhosis and other severe liver disease and still have a normal AST level.

- People with hepatitis C may see their AST levels fluctuate.

(Note: AST is also known as aspartate transaminase.)

Normal Level in Adults: Less Than 20 (µmol/L)

Bilirubin is a yellowish substance in the blood created by the breakdown (destruction) of hemoglobin, a major component of red blood cells.

As red blood cells age, they break down naturally in your body. These destroyed cells release hemoglobin, which is converted to bilirubin. The bilirubin then passes on to your liver. Your liver excretes bilirubin in fluid called bile. If your liver is malfunctioning, it won’t excrete bilirubin properly.

High levels of bilirubin can cause jaundice: yellowing skin and eyes, darker urine, and lighter-coloured bowel movements.

Explanation of Test Results

- If your bilirubin level is higher than normal, it may mean that your liver is not working properly.

- When bilirubin remains high for prolonged periods, it usually indicates severe liver disease and possibly cirrhosis.

- Elevated bilirubin levels can be caused by reasons other than liver disease.

Normal Level in Adults: 1.0

An INR test measures how quickly your blood forms a clot compared with normal clotting time. You may also hear INR called PT (prothrombin time) or PT INR. These are all the same test.

Explanation of Test Results

- In cases of serious liver disease and cirrhosis, your liver may not produce the normal amount of proteins. Then your blood can’t clot normally. Each INR increase of 0.1 above the norm means the blood is slightly thinner and taking longer to clot.

- High INR usually means your liver isn’t working at its best because it’s not supporting normal blood clotting.

- Some cirrhosis patients take a drug called Coumadin (warfarin), which elevates INR for the express purpose of “thinning” the blood.

Normal Level in Adults: 35 – 50 g/L (Grams Per Litre)

Albumin is a common protein found in the blood and produced only in your liver. It has a variety of functions, one of which is to prevent fluid leaking from blood vessels into tissues.

If your albumin levels are lower than normal, it can suggest chronic liver disease or cirrhosis. Many conditions other than liver disease may also cause low albumin levels.

Explanation of Test Results

- Albumin levels can fluctuate slightly in a healthy liver, but low albumin usually indicates cirrhosis (advanced liver disease).

- Low albumin can also result from kidney disease, malnutrition, or other acute illnesses.

- Very low albumin can cause edema, which means fluid buildup in the legs. When this fluid buildup occurs in your abdomen, it’s called ascites.

Normal Level in Adults: 50 – 120 (µmol/L)

Creatinine comes from the breakdown of muscle protein. It’s a body marker of kidney function. Properly functioning kidneys remove creatinine from the blood.

When creatinine levels rise gradually, there aren’t usually any symptoms. Only lab tests will detect higher levels.

Explanation of Test Results

- High creatinine means your kidneys aren’t functioning normally. This is sometimes called renal insufficiency. It can be caused by certain medications, dehydration, too high a dose of diuretics (water pills), or advanced liver disease (cirrhosis).

Electrolytes are chemicals in your body such as sodium and potassium. Your electrolyte levels must be checked often when your healthcare provider prescribes diuretics (water pills).

Normal Levels

Adult Males: 140 – 180 g/L (Grams Per Litre)

Adult Females: 120 – 160 g/L (Grams Per Litre)

Hemoglobin is a protein in red blood cells. It enables these cells to carry oxygen throughout your body.

Explanation of Test Results

- This blood test will register very low if you have internal bleeding.

Normal Level in Adults: 150 – 300 (109/L)

Platelets are cells that initiate the formation of blood clots. Labs measure platelet count as part of the complete blood count (CBC).

Explanation of Test Results

- Platelet counts in cirrhosis patients are often low. But low platelet counts can also come from other causes, including certain medications.

- When platelet count is reduced, this is known as thrombocytopenia. If you have too low a platelet count, you can’t produce normal clots and may bruise more easily.

Normal Level in Adults: 4 – 11 (109/L)

White blood cells (WBCs) are produced in the bone marrow, which is in the centre of many bones.

There are five main types of WBCs:

- basophils

- eosinophils

- lymphocytes

- monocytes

- neutrophils

Each does a slightly different job, but all of them help fight infection.

Explanation of Test Results

- Low WBC count may be caused by cirrhosis, alcohol use, medications, or other medical conditions.

- High WBC count may indicate infection.

Other Tests Relating to Cirrhosis

AFP is a protein present in people with liver disease. It’s also a tumor marker and may be used to test for liver cancer.

Explanation of Test Results

- High AFP might mean the presence of liver cancer.

- Sometimes AFP is high when there’s no cancer, but it can indicate active liver disease instead.

- High AFP should be interpreted by your doctor. It can be high because of other types of cancer or because of a normal pregnancy. Or, it may just mean you have an active liver.

- Usually, a doctor will interpret the AFP test along with images of your liver taken by ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI.

Total protein level measures a number of different blood proteins. It can be divided into the albumin and globulin fractions.

Explanation of Test Results

- Low total protein levels can occur because of impaired liver function.

Hepatitis Tests

A positive result means you’ve been infected with hepatitis A in the past or were vaccinated against hepatitis A. Therefore, you’re immune from hepatitis A infection in the future.

Explanation of Test Results

- A positive test result for Anti-HBc means you’ve been exposed to hepatitis B and have developed an antibody to just one part of the virus. This antibody does not give you immunity.

- You need more tests to find out if you have the disease.

Explanation of Test Results

- A positive test result for HBeAg means you may have very active hepatitis B and should be followed closely by your doctor. You may also need to take hepatitis B medications.

- You may be very contagious to others.

Explanation of Test Results

- A positive test result shows you have antibodies to hepatitis B and are immune to this virus.

- This could be from a natural infection or vaccination.

Explanation of Test Results

- A positive test result for HBsAg shows you are actively infected with hepatitis B.

- Your infection could be acute (a recent infection) or chronic (been there a long time, even decades).

- You could infect others, especially sexual partners.

Explanation of Test Results

- A positive result for Anti-HCV means you’ve been exposed to the hepatitis C virus. Another important test, an HCV RNA, must then be performed to find out if the virus is still in your body.

- Being positive for the Anti-HCV test does not mean you’re immune. You could be infected with hepatitis C again.

Explanation of Test Results

- If your Anti-HCV test is positive, your healthcare providers will perform the HCV RNA test next to see if you still have the virus in your body.

- A positive test result for HCV RNA means you have chronic hepatitis C. You may develop health problems from the virus.

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References: