Causes

The causes of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) remain unknown. But current evidence suggests that PBC occurs in people with a genetic predisposition—in other words, there may be a hereditary factor. However, there may also be other factors that combine with genetics to trigger the disease.

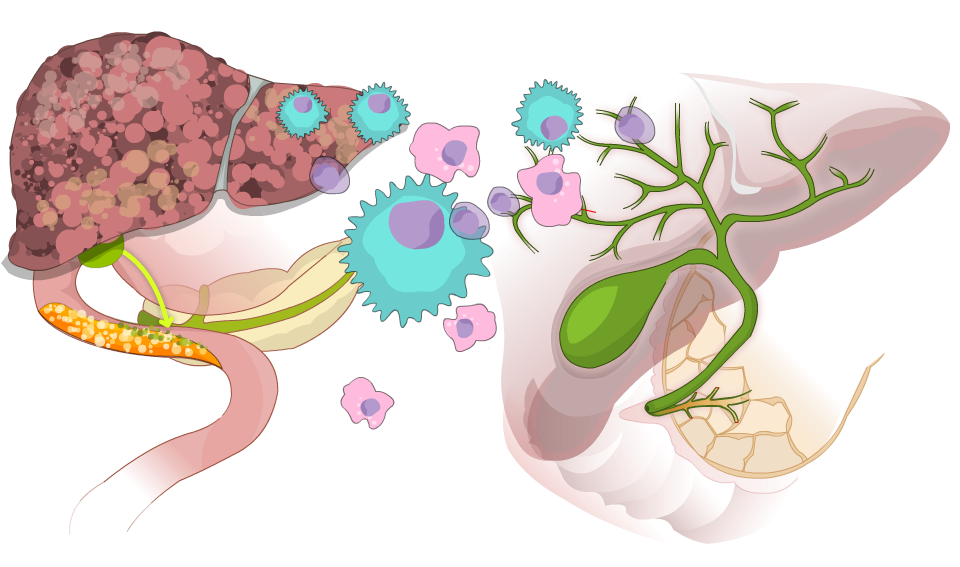

Medical scientists believe that PBC is an autoimmune disease. This means that your immune system, which protects against infections and cancer, mistakes cells in the bile ducts as being abnormal and attacks them. (The bile ducts are small tubes that bile flows through from within the liver to the gallbladder and intestines.) Some factors—such as an infection or some form of toxic exposure from the environment—may trigger your immune system into making this mistake.

PBC usually develops and progresses slowly, which means that liver damage typically gets worse over a long period of time. Medication can slow this progression, especially if you get treated early. It’s important to note that PBC is not caused by alcohol consumption.

PBC used to be known as primary biliary cirrhosis.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of PBC are fatigue and itching in any part of the body.

Many people have chronic fatigue. This can range from mild to disabling.

Itching, which is referred to medically as pruritus, can also range from mild to intense. It can be unrelenting to the point of creating stress for some patients. It often occurs on palms or soles of the feet and may be the result of the liver’s inability to process bile.

Additional PBC symptoms might include:

- gradual darkening of the skin

- small yellow raised areas under the skin (usually at the inside corners of the eyes)

Other symptoms not directly related to PBC are also often reported by people with PBC:

- arthritis

- dry membranes (nose, eyes, mouth, vagina)

- fingers and/or toes that change colour in the cold (Raynaud’s disease)

- thyroid problems

If liver damage gets worse, other symptoms may appear. These can affect parts of your body outside your liver. These symptoms are the same as for advanced liver disease from any cause.

Many people with PBC never develop any symptoms related to the disease.

Diagnosis

PBC is usually diagnosed with the following blood tests:

- Antimitochondrial Antibody (AMA). An antibody is a protein made by your body’s immune system to attack an “invader.” AMA is an important indicator of PBC.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP or Alk-Phos). Another sign of PBC is increased levels of ALP (also commonly called alk-phos). Alk-phos is an enzyme released into the blood by damaged bile ducts.

- Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) and Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST). Increased levels of these enzymes may not be as common in PBC as increased alk-phos. They measure inflammation relating mainly to liver cell damage or destruction rather than cell damage in the bile ducts. (Note: ALT is also known as alanine transaminase. AST is also known as aspartate transaminase.)

- Immunoglobulin (IgM). Increased levels of IgM can also be an indicator of PBC.

Other tests might include:

- Abdominal ultrasound. This is done to check the condition of the bile ducts and ensure there’s no other cause of decreased bile flow out of the liver.

- Liver biopsy. Doctors use this test to view the condition of the liver at the cellular level.

Treatment

PBC is a chronic liver disease: a lasting condition that can be controlled in most people but not cured. The prognosis for people with PBC has improved over the last two decades due to earlier diagnosis and improved treatment. Early access to treatment can delay the progression of the disease. Treatment improves outcomes for people with PBC, and sometimes, it can even improve outcomes so that they are similar to people without the disease.

Medications

A drug called ursodeoxycholic acid (also called UDCA or URSO) mimics a bile acid your body produces naturally. URSO can improve liver function and slow the onset of fibrosis (scar tissue) in the liver. In turn, this can delay or eliminate the possibility of liver failure and the need for a liver transplant. 80 to 90% of people with PBC on URSO manage to avoid the need for a liver transplant after 10 years. Patients usually take this drug indefinitely. Fortunately, it’s well tolerated and has minimal side effects.

Researchers are working on new medicines to treat PBC, typically for use with URSO. Obeticholic acid (OCA), a manufactured bile acid that helps reduce liver inflammation and cholestasis (restricted bile flow), is available in Canada.

To help relieve itching (pruritus), a common symptom, your doctor may prescribe various medications such as cholestyramine, antihistamines, or other drugs such as naltrexone or rifampicin. For people with extreme itching, doctors will occasionally prescribe ultraviolet light therapy.

Other Treatments

Your doctor will also discuss other treatments for you to consider. These can include calcium and vitamin D to preserve your bone health. It may also involve other fat-soluble vitamin supplements and treatments for managing symptoms such as dry eyes, mouth, or vagina.

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References: