When to Get Help

Contact your healthcare provider right away or go to the emergency department if you have:

- trouble breathing

- new or sharp pain in your belly that doesn’t go away

- a fever

- nausea and vomiting

We have a single page handout for you that covers the most important aspects of Ascites.

What is Ascites?

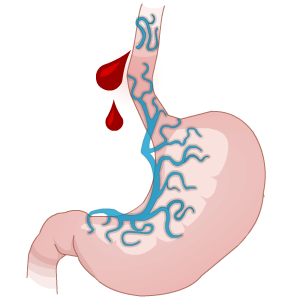

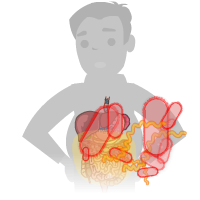

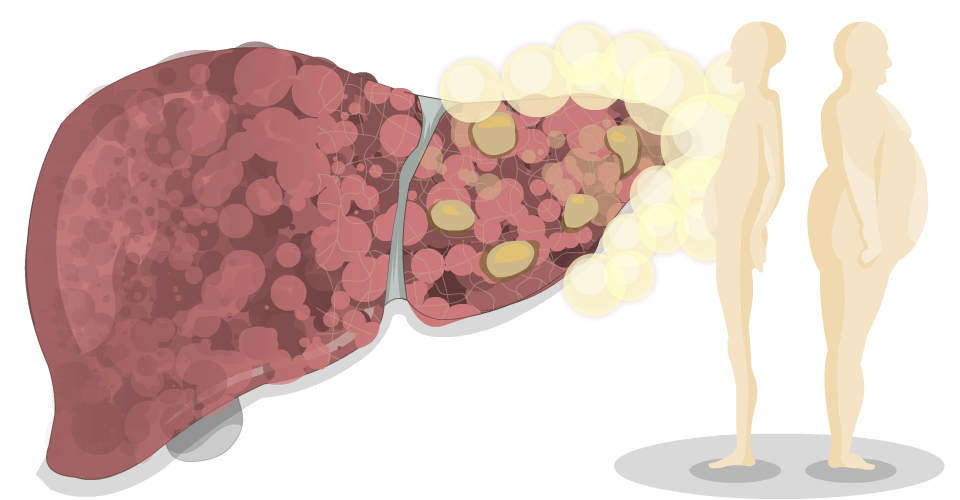

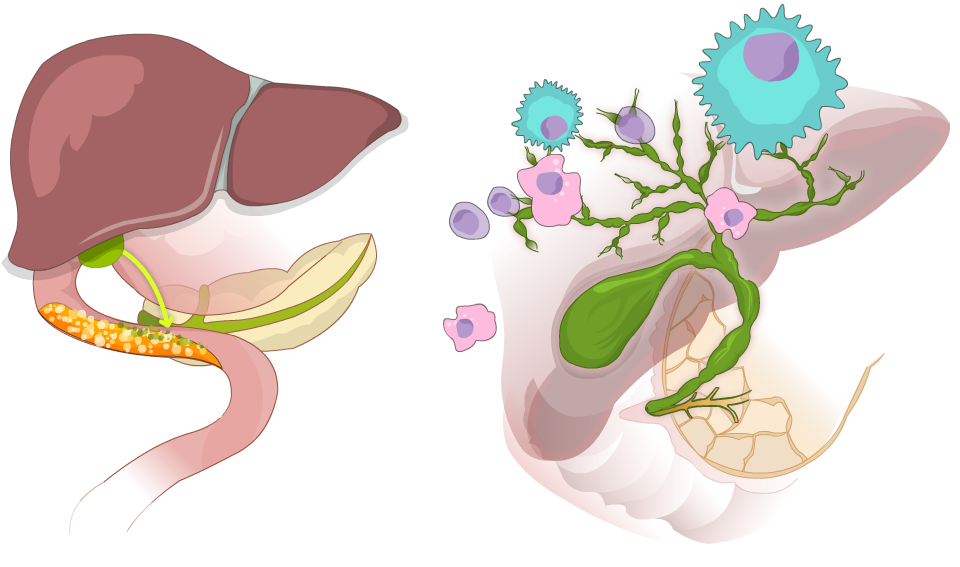

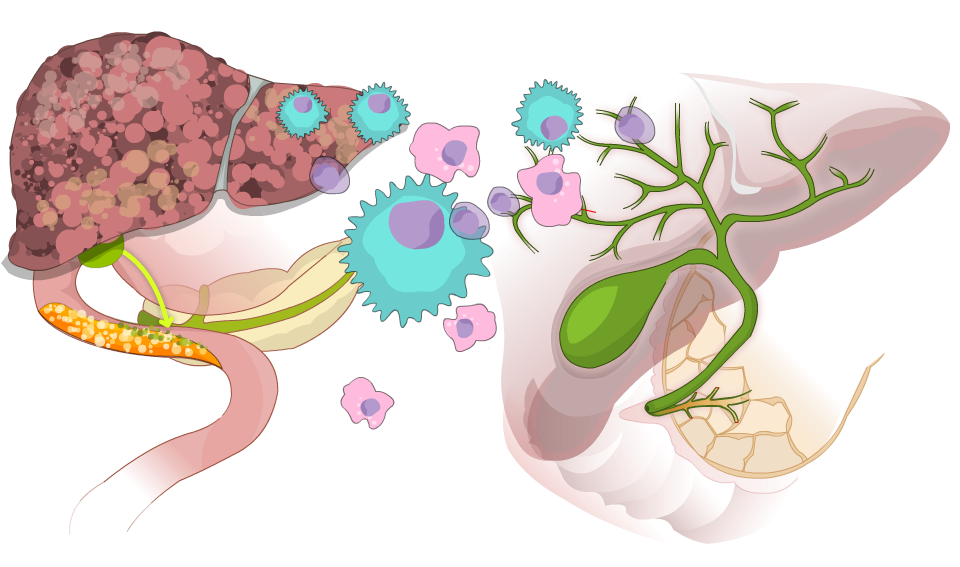

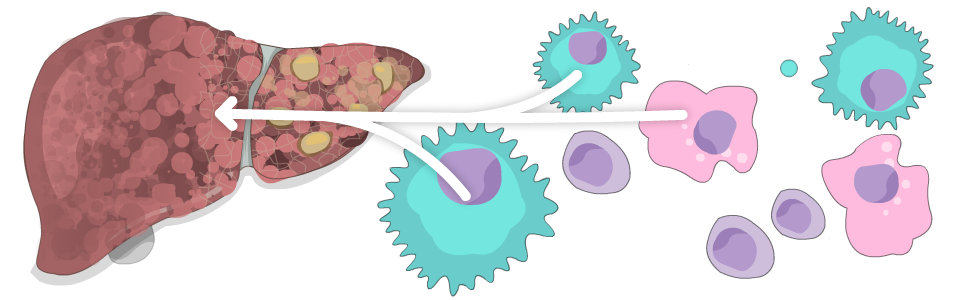

The most common major complication of cirrhosis is ascites (pronounced “a-sigh-tees”). When pressure in the portal vein gets too high (called portal hypertension), fluid leaks out and builds up. This can make your abdomen enlarge like a balloon filled with water. Ascites might be diagnosed with a physical exam. You may need other tests like an ultrasound (to look for fluid) or paracentesis (to take a sample of the fluid for testing).

The most common major complication of cirrhosis is ascites (pronounced “a-sigh-tees”). When pressure in the portal vein gets too high (called portal hypertension), fluid leaks out and builds up. This can make your abdomen enlarge like a balloon filled with water. Ascites might be diagnosed with a physical exam. You may need other tests like an ultrasound (to look for fluid) or paracentesis (to take a sample of the fluid for testing).

Ascites can be very uncomfortable. Eating can be a problem because you have less room for food. Even breathing can be a problem, especially when you’re lying down. It can also lead to fluid buildup in the space around your lungs (called pleural effusion or hepatic hydrothorax), or abdominal hernias – especially umbilical hernias (when tissue from inside the abdomen bulges out through a weak spot in the navel or belly button).

The most dangerous problem associated with ascites is an infection called spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), which can be life-threatening. Some symptoms of SBP are fever, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, or confusion. If you get spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), you will need antibiotics to treat it. After you recover, you will probably be prescribed another antibiotic to reduce your risk of getting SBP again.

Treatment

Treatment for ascites caused by cirrhosis can include more than one of the options listed below.

Low Sodium (Salt) Diet

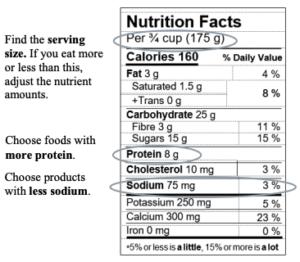

Restricting sodium is an important part of ascites treatment. Too much sodium can make your body hold on to extra fluid. This fluid can pool in your belly, chest and legs. Eating foods with less sodium can help control ascites.

- Aim to eat less than 2000 mg of sodium a day.

- One teaspoon of salt has about 2300 mg of sodium.

- All types of salt contain the same amount of sodium, including table salt, sea salt, and Himalayan salt.

Tips to reduce sodium:

- At first, foods may taste bland. Over time, your taste buds get used to less salt.

- Don’t add salt to your food while cooking or at the table.

- Choose fresh, unprocessed, and homemade foods.

- Eat less processed, packaged, or restaurant foods.

- Limit condiments and sauces (ketchup, mustard, soy sauce, gravies, salad dressings).

- Limit pickled foods, olives, chutneys, and dips.

- To boost flavours, try adding spices, seasoning mixes with no salt added, lemon, lime, vinegar, fresh or dry herbs, garlic, or onions

To access liver-friendly recipes and cooking videos, click here

Read food labels

Diuretic Medicine

Diuretic medicines such as furosemide and spironolactone can also help to get rid of the fluid that has built up in the abdomen (belly) and other parts of the body. If you have ascites, your doctor may prescribe a diuretic for you to take.

If you are taking diuretics, it is important to weigh yourself daily to monitor the effect of diuretics. One litre of ascites weighs about 2.2 pounds (1 kg). Gradual weight loss is a sign of decreasing ascites – this is expected and desired when diuretics are first started. Losing weight too quickly can be dangerous.

You should also have your blood work checked as recommended by your healthcare team because diuretics can effect your kidneys and electrolyte levels. Your dose of diuretics can be adjusted by your healthcare team if you are losing weight too quickly, having side effects, or they don’t seem to be working.

Let your healthcare team know if you are experiencing:

- dizziness

- a decrease in urination

- confusion or sleepiness

- have ongoing or worsening swelling in your abdomen (belly)

- are losing weight too quickly: 2 pounds (0.9 kg) or more in a day, for 2 days in a row, OR more than 7 pounds (3.2 kg) in a week

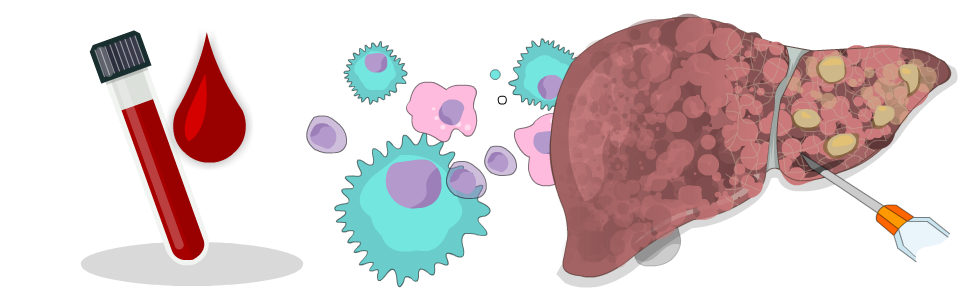

Paracentesis

Paracentesis is a procedure used to remove ascites fluid.

Sometimes paracentesis is used to take a sample of the fluid for determining why it’s building up. Paracentesis might also be used if you have cirrhosis and the following circumstances:

- You have severe ascites. It’s causing extreme discomfort, abdominal pain, and difficulty breathing. A paracentesis treatment may relieve the discomfort before you begin treatment with one or more diuretics.

- You haven’t responded to the standard ascites treatment of a low-salt diet and diuretic medicines, or your body is unable to tolerate diuretic medications. This is the case in less than 10% of people with ascites. In this situation, you may require paracentesis repeatedly.

- Your doctor suspects the fluid is infected.

Other Treatments

Your healthcare team may recommend other treatment options. Options available to you will depend on lots of different factors like your age, other medical conditions and how sick your liver is. Some other treatment options might include:

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). This procedure that involves inserting a shunt to decrease portal hypertension by redirecting blood flow around the liver.

- Liver transplant. This is a major surgery where your liver is removed and replaced with a donor liver.

- Indwelling abdominal catheter. This is a special type of catheter that’s left in place for ongoing fluid drainage.

Self Care Tips:

- weigh yourself each morning before breakfast, before you drink anything or take medicine, and after you pee (urinate).

- Keep track of your weight in a notebook or app on your phone. Most people will see changes in weight readings, even before they notice changes in how their abdomen looks or feels.

- If you are taking diuretics (water pills), have your blood tests done regularly to check your kidneys and electrolytes as recommended by your health team.

Let your healthcare provider know if you:

- feel dizzy

- are not passing enough urine

- are losing weight too quickly: 2 pounds (0.9 kg) or more in a day, for 2 days in a row, OR more than 7 pounds (3.2 kg) in a week

- have ongoing or worsening swelling in your abdomen (belly)

- gain 2 pounds (0.9 kg) or more in a day, for 2 days in a row, OR gain 5 pounds (2.3 kg) in a week

References:

The information on this page was adapted (with permission) from the references below, by the Cirrhosis Care Alberta project team (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and patient advisors).

This information is not intended to replace advice from your healthcare team. They know your medical situation best. Always follow your healthcare team’s advice.

References: