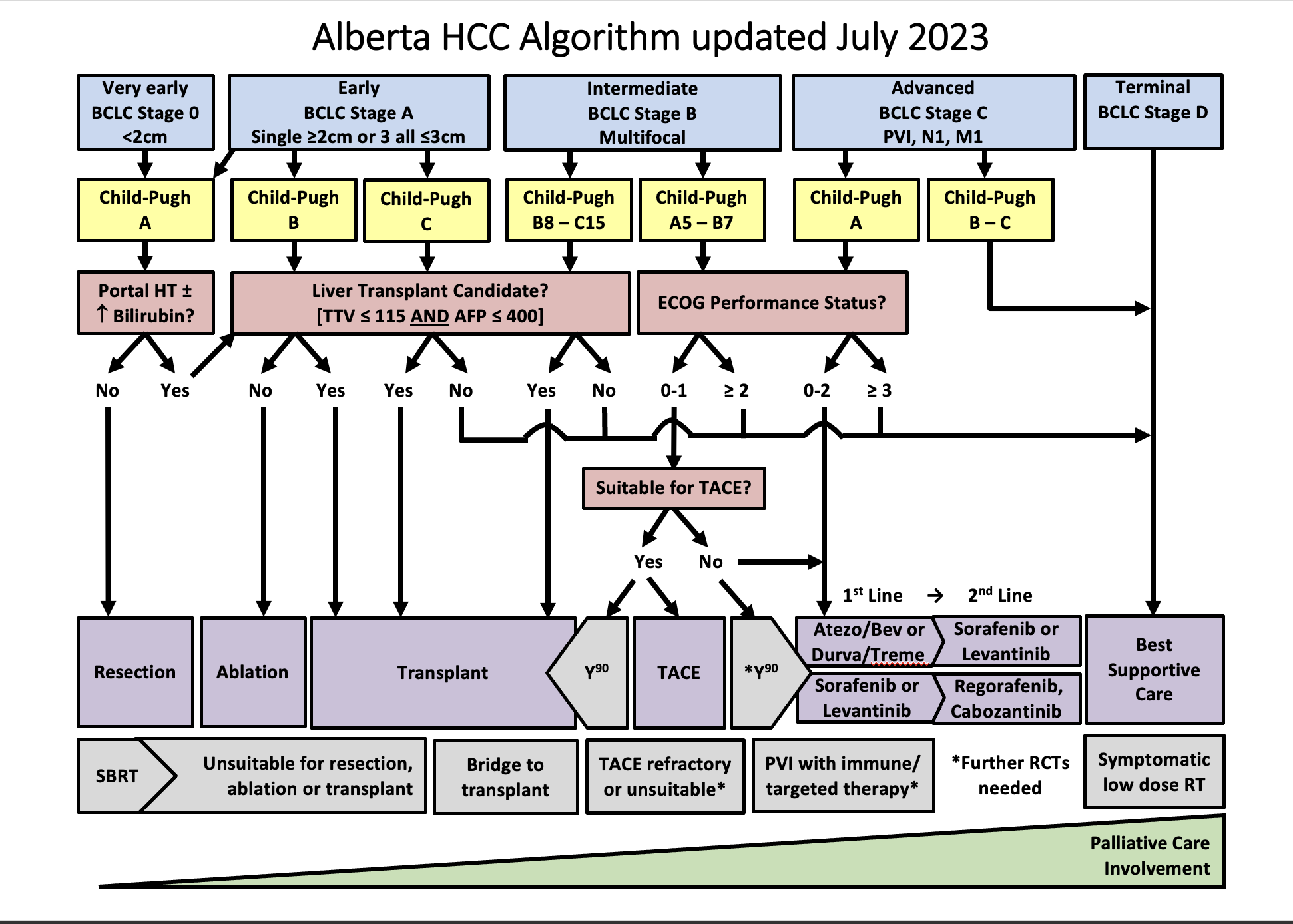

Defined as a single lesion <2 cm in a patient with preserved liver function, without vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, or cancer related symptoms (PS=0). The most recommended treatment for these patients is ablation, but resection is another option. Ablation and resection offer similar survival rates. These patients are not granted exception points for liver transplantation. Other treatment options, when ablation and resection are not possible, are TACE, TARE, and SBRT.

Defined as a single lesion >2cm, or a multifocal HCC with up to 3 nodules, each < 3 cm. In addition, patients need to have preserved liver function and should be free of vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread and/or cancer related symptoms (PS=0). The preferred treatment for single lesions, if possible, is resection. Liver transplant is the treatment of choice for patients with multifocal HCC or with solitary HCC < 5 cm not amenable to resection; patients that are not eligible for liver transplant should undergo ablation. If a patient with HCC is expected to be on the waiting list for > 6 months, the HCC should receive treatment as a bridging strategy to liver transplant to prevent HCC progression beyond transplant criteria. There is evidence to support the use of ablation, TACE, or TARE, or SBRT as a bridge to liver transplant. Single lesions < 8 cm can also be treated with TARE. Another alternative, when the previous strategies are not feasible, is the use of SBRT.

Refers to patients with preserved liver function, without vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, or cancer related symptoms (PS=0), but with a tumor burden beyond that of stage A. This is a very heterogeneous stage, and can be subdivided in 3 groups:

1.Patients with a tumor burden beyond transplant criteria, but with a well defined disease that is within criteria to allow downstaging strategies. These criteria are defined by each center or transplant program. In Alberta, a patient can be considered for down-staging IF the TTV is ≤ 250 cm³, regardless of AFP. Following downstaging, a patient can be considered for transplantation if TTV ≤ 115 cm³ and AFP ≤400 ug/mL for 6 months. Downstaging can be achieved with ablation, TACE, or TARE.

2. Patients with a well defined tumor burden that is amenable to TACE, and not considered for LT. Another treatment option is TARE, which is better suited for single lesions. SBRT can also be considered.

3.Patients with diffuse, infiltrative, and/or extensive tumor burden not suitable for TACE. These patients are better served with systemic therapy.

Defined by vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread and/or minor cancer related symptoms (PS=1-2). These patients should be treated with systemic therapy.

Comprises patients with compromised liver function not being considered for LT, and/or patients with major cancer-related symptoms(PS>2). These patients should receive best supportive care.