Top tips:

- Breathlessness as a symptom is a subjective sensation.

- Breathlessness can be caused by general causes or cirrhosis specific causes (e.g. hepatopulmonary syndrome)

- Treat breathlessness if it is affecting quality of life and function. Take into account goals of care.

- Opioid therapy may be helpful to manage moderate to severe breathlessness in the last days to weeks of life.

Check out the bottom of the page for short videos from Dr. Sarah Burton-Macleod and Dr. Christopher Woodrell.

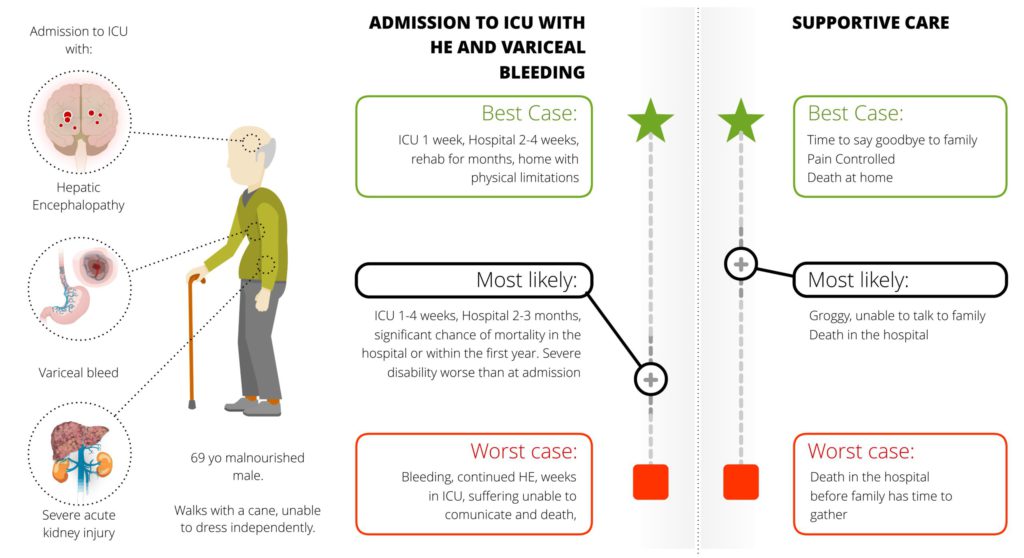

Investigation and treatment of breathlessness should be in keeping with the patient’s goals of care.

- Ascites causing diaphragmatic compromise

- Physical deconditioning (See CCAB exercise page)

Examples of other potential causes:

- Hepatic hydrothorax (transudative pleural effusion) (See CCAB hydrothorax page)

- Other cardiopulmonary diseases

- Anxiety (See CCAB Anxiety page)

- Anemia

Cirrhosis related causes – A liver specialist may need to be consulted. Some patients may meet criteria for liver transplantation or specialized treatments may be needed (e.g. hepatopulmonary syndrome, portopulmonary hypertension).

- Sit in an upright position (45 degrees)

- Position next to an open window

- Have a fan blow air gently across the face (stimulation of the trigeminal nerve V2 branch has central inhibitory effects on dyspnea)

- Maintain humidity in room

- Supplemental oxygen – the patient must be hypoxic at rest in order to qualify for coverage

- Meditation, mindfulness, music and/or relaxation therapy

- Provide reassurance

Breathlessness handout in development.

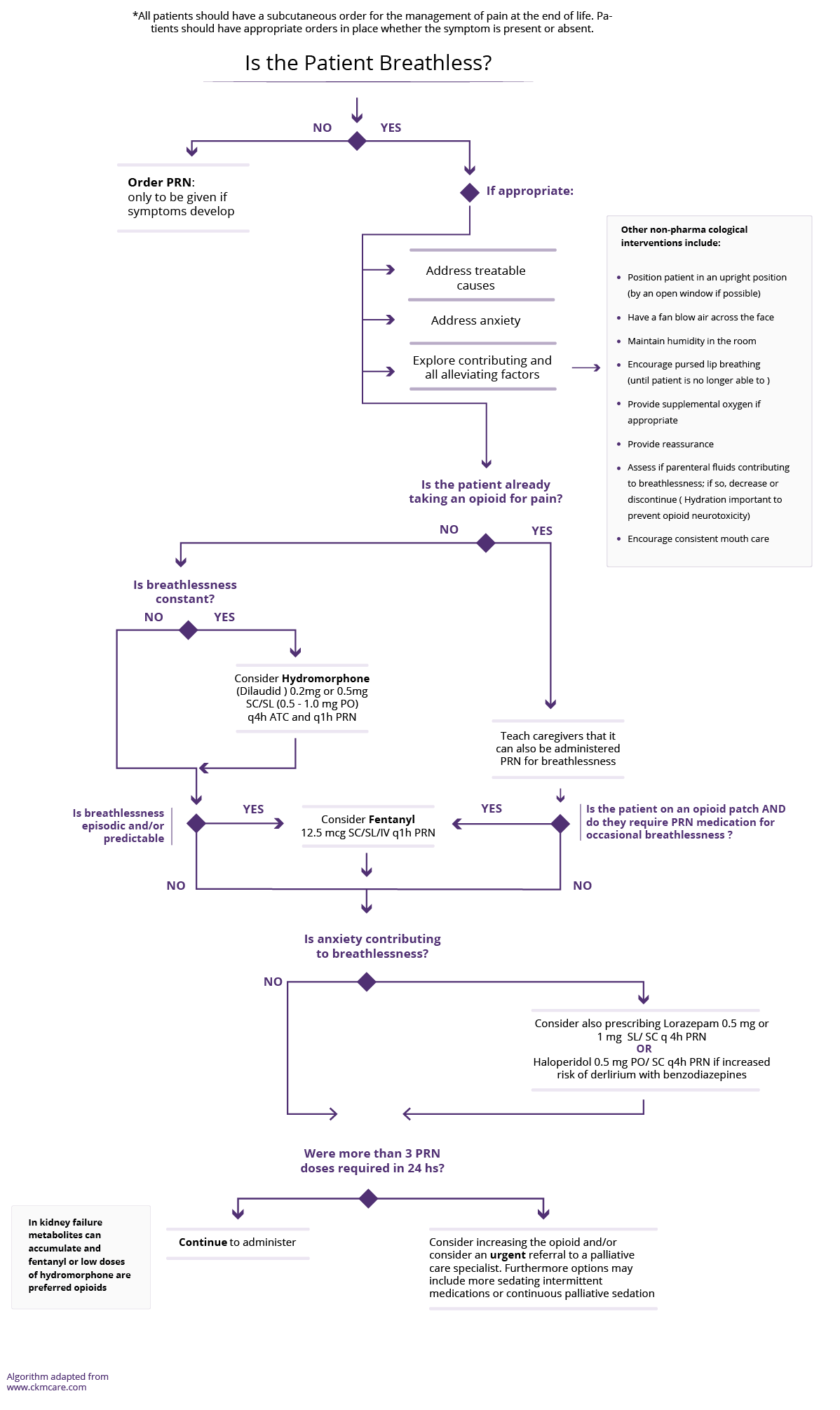

Always weigh the risks and benefits of opioids with the patients in the context of their goals of care.

- Always start at a lower dose and titrate to effectiveness.

- If the patient is already taking an opioid for pain, educate them that it can also be used for the management of breathlessness

- Monitor closely for signs of opioid toxicity. Prescribe laxatives to avoid constipation

If shortness of breath is episodic and primarily associated with a specific activity, consider

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl | 12.5mcg SC/SL/intranasal q1h PRN |

|

If shortness of breath is constant or more unpredictable in nature, consider

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 0.5mg PO (or 0.2mg SC) q4h ATC and q1h PRN Max: 5 mg PO QID |

|

- At End of life, as the patient’s condition deteriorates, opioid titration will likely need to be escalated for dyspnea.

- Consider Palliative Care consultation as required.

See the End of Life Breathlessness Algorithm for the last Days/Weeks of life.

This section was adapted from content using the following evidence based resources in combination with expert consensus. The presented information is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient’s care.

Authors (Alphabetical): Amanda Brisebois, Sarah Burton-Macleod, Ingrid DeKock , Martin Labrie, Adriana Lazarescu, Noush Mirhosseini, Mino Mitri, Kinjal Patel, Aynharan Sinnarajah, Puneeta Tandon

Thank you to pharmacists Omer Ghutmy and Meghan Mior for their help with reviewing these pages.

For a comprehensive review on breathlessness, please refer to the links below.

- Goals of care

- Anxiety

- Physical Activity

- Hydrothorax

- Ascites

- Opioid Considerations document: In development

References:

- Davison SN on behalf of the Kidney Supportive Care Research Group. Conservative Kidney Management Pathway; Available from: https//:www.CKMcare.com.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: [email protected]; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018 Aug;69(2):406-460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. Epub 2018 Apr 10. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2018 Nov;69(5):1207. PMID: 29653741.

- Krowka MJ, Fallon MB, Kawut SM, Fuhrmann V, Heimbach JK, Ramsay MA, Sitbon O, Sokol RJ. International Liver Transplant Society Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis and Management of Hepatopulmonary Syndrome and Portopulmonary Hypertension. Transplantation. 2016 Jul;100(7):1440-52. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001229. PMID: 27326810.

- Walling AM, Wenger N. Palliative care for patients with end-stage liver disease. In Uptodate, Mar 06, 2020.