To download the complete "Nutrition in Cirrhosis Guide" (40 pages) as a .pdf file, click here.

The Guide was made possible from extensive feedback from patients, and their family & friends, who attend The Cirrhosis Care Clinic (TCCC) at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

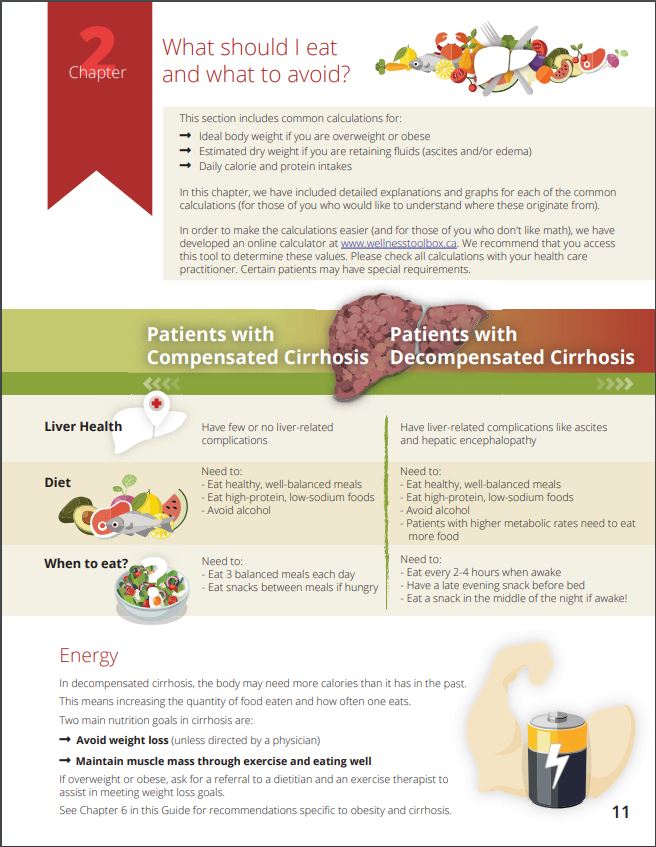

This Guide covers general topics relevant to all patients with cirrhosis. Specific nutrition issues are also addressed that may be helpful at other times. The Guide is a tool for use throughout your cirrhosis journey.

The Guide is intended to be read a few pages at a time, beginning with those most important to your health or of interest to you.

The recipes (Chapter 4) are suitable for all individuals and can be modified to accommodate food allergies, dietary restrictions, and preferences.

Funding for the Guide’s creation was obtained from a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Alberta Innovates. Alberta Health Services provided protected time to V DenHeyer.

The following organizations provided support in the form of unrestricted educational grants to support the Guide:

Peer review regarding the content and format of the Guide was obtained from registered dietitians (RDs) and gastroenterologists in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver. Additional input was obtained from experts across North America and Europe. Thank you for your valuable input and assistance.

If any portion of the Guide is used in research, communications, or patient care, please use the following citation:

Tandon P, DenHeyer V, Ismond KP, Kowalczewski J, Raman M, Eslamparast T, Bémeur C, Rose C. The Nutrition in Cirrhosis Guide. University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. 2018. pp. 1- 40.

The Nutrition in Cirrhosis Guide may be reproduced for non-commercial use as is and in its entirety without further permission. Adaptations, modifications, unofficial translations, and/or commercial use of The Nutrition in Cirrhosis Guide are strictly prohibited without prior permission.

The Cirrhosis Care Clinic

University of Alberta

Edmonton, AB, Canada T6G 2X8

www.wellnesstoolbox.ca